Thursday, February 25, 2010

Winnipeg’s North End, Yesterday and Today

This is a great article from Canadian Dimension Magazine... I posted a comment which is at the very bottom.

Alan

Winnipeg’s North End

Yesterday and Today

By: Jim Silver

January 7th 2010

http://canadiandimension.com/articles/2674/

Winnipeg’s Historic North End. Photo Courtesy of The Winnipeg Tribune / University of Manitoba Archives.

Elsie Strewchuk stands behind the counter of the North Main Groceteria that she and her husband opened in 1954. Photo Courtesy of The Winnipeg Tribune / University of Manitoba Archives.

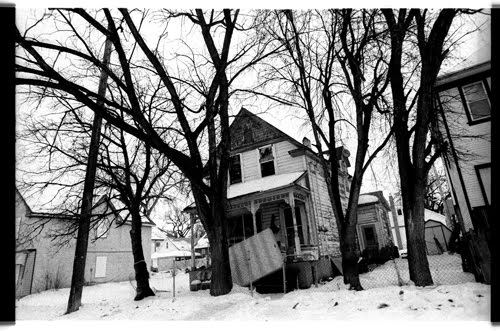

Poverty in the North End today. Photo by Jon Schledewitz

Winnipeg’s historic North End was a contradictory place. Poverty was widespread and deep; out of its midst grew a rich and vibrant culture. Today’s North End is similar in many respects — deep poverty and racism, and an emergent culture of resistance, for example — yet different in important ways.

Poverty in Winnipeg’s Historic North End

After 1896 Eastern European immigrants arrived in large numbers in Winnipeg, settling in the North End to work in the vast rail yards and associated industries. Housing was inadequate and terribly overcrowded. The 1908/09 Annual Report of All-Peoples’ Mission, then headed by J. S. Woodsworth, said of a part of its North End neighbourhood: “in 41 houses there were 120 ‘families,’ consisting of 837 people living in 286 rooms,” more than 20 people per house. Overcrowding, plus half the North End houses not being connected to the water supply, produced disease: in 1904 and 1905 Winnipeg had more deaths from typhoid than any North American city. A 1913 study by Woodsworth found that a “normal standard of living” required wages of $1,200 per year; many in the North End were earning less than half that.

Most people were working; they just didn’t get paid enough. Others worked seasonal jobs on farms or railway construction and endured cold, hungry winters in Winnipeg.

Winnipeg was deeply segregated, a city divided, the North End cut off from the rest of the city by the vast CPR yards and distinguished by its “foreign” character. A 1912 publication described the North End as “practically a district apart from the city,” adding that “those who located north of the tracks were not of a desirable character.” The largely Eastern European working class residents of the North End were called “dumb hunkies,” “bohunks,” Polacks; anti-semitism was rampant.

In Under the Ribs of Death, John Marlyn’s novel set in early twentieth Winnipeg, Sandor Hunyadi, a young Hungarian immigrant, lives in the North End, described as “a mean and dirty clutter … a howling chaos … a heap seething with unwashed children, sick men in grey underwear, vast sweating women in vaster petticoats.” When the young Sandor visits Crescentwood, the south end home of those of Anglo-Saxon descent who controlled the political and economic resources of the city, he was shocked to see that “the boulevards ran wide and spacious to the very doors of the houses. And these houses were like palaces, great and stately, surrounded by their own private parks and gardens. On every side there was something to wonder at.”

Much was extremely positive about the North End. Selkirk Ave was a thriving commercial street with a dazzling variety of shops and stores whose owners typically spoke several Eastern European languages. A rich and varied cultural life characterized the North End: newspapers published in many European languages; literary associations, drama societies, and sports clubs; a wide range of alternative schools; and according to one author, “a music teacher in every block in the North End to give the Jewish, Ukrainian, and Polish kids massive degrees of musical instruction weekly.” There was a thriving co-op sector, mutual aid societies, a labour temple, and radical politics of a bewildering variety of kinds.

Most of this was invisible to those outside the North End, but as Roz Usiskin has put it, from this vibrant culture North End residents “derived a dignity denied them by the dominant society.”

Post-War Change in the North End

In the post-Second World Large numbers of North End residents who could afford to do so moved to the larger, newer houses and greener spaces of the suburbs. Businesses andcultural organizations followed; economic and cultural life in the North End atrophied. Housing prices dropped; many became rental properties, some owned by slum landlords.

By the late 1960s-1970s manufacturing began to leave, and the character of the labour market shifted, with full-time unionized industrial jobs gradually being replaced by part-time, non-union, low-wage service sector jobs.

Just as these broad social forces — suburbanizationand de-industrialization — were unfolding, Aboriginal people began migrating to western Canadian cities, and especially Winnipeg, starting in the 1960s and growing by the decade. In 1951 there were 210 Aboriginal people resident in Winnipeg; in 1961 there were 1,082. By 2006 there were 68,380, the largest urban Aboriginal population in Canada. Many Aboriginal people located in the North End, attracted by cheap rental housing. When they arrived they were, generally speaking, ill-prepared for modern urban life, the result of a century of marginalization, colonization, and the damage inflicted by the residential schools. They arrived just as the good jobs were leaving, to the suburbs or out of Winnipeg entirely. And upon their arrival they faced a wall of racism.

Aboriginal people have replaced Eastern European immigrants as the poor and frequently reviled residents of the North End. They face the same racism and exclusion today that the newly-arrived Eastern European workers and their families did early in the twentieth century. They experience similarly inadequate and over-crowded housing conditions — the result of the severe shortage of low-income rental housing all across Canada that is accentuated in Winnipeg’s now sprawling inner city.

They have suffered racist abuse for decades. In a 1962 Winnipeg Tribune story, Jarvis Ave., just north of the CPR yards and previously the heart of the pre-Second World War Jewish North End, was described as “the worst street in the entire city.” Houses had long been little more than shacks; many of the small lots had two or more dwellings squeezed onto them. The Tribune story began: “The police, with ponderous legal irony, call it Jarvis Boulevard. Others, with more bitterness, have called it Tomahawk Row.” Aboriginal newcomers had located there, in search of low-cost housing. Their socio-economic circumstances were the root cause of problems in the area.

But, like their Eastern European working class predecessors who had occupied the same neighbourhoods before them, they were blamed for their poverty. A half-century earlier, in 1912, Winnipeg’s Associated Charities Bureau had written, referring to the Eastern European working class immigrants squeezed into inadequate North End housing and underpaid as they were, that “the large majority of applications for relief are caused by thriftlessness, mismanagement, unemployment due to incompetence, immorality, desertion of the family and domestic quarrels.” Such simplistic and stereotypical claims echo across today’s North End.

These things about Winnipeg’s North End have not changed. It is home to deep and widespread poverty; those who are poor are reviled and blamed for their own fate; and the North End remains spatially and socially segregated from the rest of the city. Many in Winnipeg do not venture into today’s North End; most are largely ignorant of life in the North End; it has ever been thus.

It’s Still the Same, but Different

Whereas the poverty of the early twentieth century North End was a working class phenomenon, today, because of dramatic shifts in the global economy, a much higher proportion of those in poverty are the jobless poor, largely outside of and in many cases with little or no experience of the paid labour force. This is disproportionately the case for Aboriginal youth, and is a source of many problems. Massive, publicly funded job creation is needed.

The North End poor of the early twentieth century typically lived in and benefited from intact, two-parent families, and ethnic cultures that were a source of strength and pride. Today, a much higher proportion of those who are poor live in families and communities that are less strong and resilient than was the case in the past, and in many cases their cultures have been seriously damaged. In the case of Aboriginal people, this is the result of the historic and contemporary process of colonization, by which the Canadian state set out deliberately to destroy Aboriginal families and cultures.

The route out of poverty taken by many of the descendants of the Eastern European working class is less readily available to the disproportionate numbers of today’s North End poor who are Aboriginal. Eastern Europeans were able to, and wanted to, assimilate into the dominant culture. Aboriginal people are less able to assimilate, less able to escape racism than their White predecessors in the North End, and less willing to do so.

The poverty of today’s North End has changed dramatically because of the intensified crime that plagues the inner city. Street gangs, the illegal drug trade, and damage done to families and cultures, and the almost complete disconnection of large numbers of young people from the labour market, have created a serious problem of crime and violence that is qualitatively different, and worse, than what existed in the North End during earlier periods of the twentieth century.

Finally, the poverty of today’s North End is experienced by many as a sense of hopelessness, of deep and dark despair. Inadequate housing, deep poverty, the prevailing crime and violence, the absence of jobs that pay a wage sufficient to support a family, have created a “spiritual” malaise among many that is particularly debilitating.

In many respects, today’s North End is unchanged from that of the early part of the twentieth century: deep poverty; widespread racism directed at the poor; their spatial segregation in a devalued part of the city. In other respects, it is different, perhaps even worse: the disconnection from a changed labour market; the erosion, in many cases, of families and cultures; the widespread crime and violence; the deep sense of despair and hopelessness amongst many.

Rebuilding from Within

These poverty-related problems notwithstanding, there is a dramatic process of rebuilding from within that is currently underway in Winnipeg’s North End and broader inner city. Like the vibrant culture of the early twentieth century North End, it is largely invisible to those who do not live there. It takes the form of a wide range of community-based organizations that have emerged from the ground up, and that use a community development approach to heal and empower those who are poor and have been damaged by poverty, racism, and colonization. Aboriginal people and Aboriginal women in particular are among the leaders in this work. The best of their efforts is aimed at rebuilding awareness and appreciation of their rich cultural heritage. Women’s centres of a wide variety of kinds, family resource centres, alternative educational institutions and neighbourhood development organizations are all part of an increasingly strong infrastructure of community-based organizations. Their work is creative and innovative; they hire local people thereby creating employment opportunities; they work in a way informed by their workers’ and leaders’ own experience of poverty and racism.

This rebuilding process is slow and difficult. For every step forward, another is taken back. It would be faster and less difficult with more public sector support. The civic and federal governments are largely absent from this process. The provincial NDP government has been supportive in many important ways. They have not done and still do not do enough to nurture and support this indigenous rebuilding process, but they have been quite supportive in some very important ways, and would be likely to be more so if they thought that there was public support for a stronger anti-poverty strategy.

The North End and the Left

The anti-poverty strategy that has emerged out of Winnipeg’s North End and broader inner city over the past quarter-century has not taken a form familiar to most leftist readers of Canadian Dimension. It has been and is being built by the poor themselves, and has taken a form that they have defined, and that has grown out of their realities. The labour movement is largely absent from this struggle; the far Left, to the extent that it exists at all in Winnipeg any longer, is absent from this struggle.

It is striking, however, that growing numbers of progressive young people are becoming interested in and active in this struggle. Although what follows is impressionistic, it may be that many young people recently energized by the anti-globalization movement have now turned their attention to local, community-based anti-poverty struggles in the North End and broader inner city.

If young, urban Aboriginal people were also to become politicized as part of this struggle, and were to begin to mobilize around demands related to antipoverty efforts, the pace of change would surely accelerate. There are few signs yet of that happening, and in fact an Aboriginal middle class is emerging, anxious to distance themselves from the poverty and related problems of the North End.

Yet there is deep anger in Winnipeg’s North End, the product of poverty, racism, and segregation. Much of that anger is inner-directed, in such forms as addictions and domestic abuse, but also in the form of increasingly severe street-level conflict and violence confined largely to the North End and directed largely at other North End residents, and frequently at police.

Most Winnipegers, spatially and socially segregated from the North End and its residents and steeped in stereotypes previously used to describe Eastern Europeans, are removed, in every respect, from these issues. If they could be mobilized in support of genuine, publicly-driven anti-poverty efforts, and/or if North End youth, and especially Aboriginal youth, were themselves to become politicized and direct their anger outwards, real gains could be made in the North End. Until that happens, and despite the exceptional community development efforts in the North End, change will be unbearably slow, and will come too late for many.

This article appeared in the January/February 2010 issue of Canadian Dimension magazine. SUBSCRIBE NOW to get a refreshing and provocative alternative delivered to your door 6 times a year for up to 50% off the newsstand price.

5 comments

I live in the South End of Nanaimo, which is considered the skuzziest neighborhood in the city. Yes, you do see some poor young girls in the sex trade walking down Victoria Road, and that is because men in fancy cars from the North End come looking to exploit their drug addictions which were induced by some other exploitative men. On what is considered THE worst block in this city, a couple of blocks from downtown, my friend just bought an 80 year old house, a Craftsman, which has unsurpassable charm. Three stained glass windows, original fir floors in good condition, coved ceilings, french doors with etched leaded glass panels, a sun room with windows on 3 sides, which leads to a sundeck with a sweeping view of the estuary and Gabriola Island, and spectacular sunrises which are reflected on the water. There is a walk-in closet off the master bedroom. There is a little inner courtyard outside, and a peach tree and 2 Kiwi fruit trees, and a fish pond in the yard. Next door to her live 4 men who are a brass quartet, and they have a big old boat in their backyard. My point in all this is that it is possible to find beauty and charm where you least expect it, and it doesn’t have to be about big money at all. In fact there can be something ugly about big money neighborhoods - the pretentiousness of them, and the lack of originality, spontaneity, history, and variety.

#1. Posted by Madeline Bruce, RPN in Nanaimo, B. C. on January 8th 2010 at 4:35pm

So , it would seem to me to solve the problem of poor people living in the North End, would be to double the rents to get rid of the poor .

#2. Posted by rosencrentz in winnipeg on January 28th 2010 at 6:58pm

No, that doesn’t sound nice at all. Speaking for South Nanaimo, the poorer section of Nanaimo, the price of houses and rentals is lower than the rest of Nanaimo. Gradually the old houses are being re-vamped, which makes for a very charming ambiance. As for unemployed people, many impoverished people are employed - just not getting enough hours, or enough wages. As for the chronically underpriviledged, some kind of entreprenurial initiative is needed to help them. Perhaps the teaching of new skills by retired people, which they could then market themselves, would get them on the road to a renewed self-confidence and hope for the future.

#3. Posted by Madeline Bruce, RPN in Nanaimo, B. C. on January 28th 2010 at 7:32pm

I enjoyed reading this article and found it very thoughtful. I grew up in the North End in the 1950s and 60s, spending all my time hanging around at the Sals and Sportsman’s. I am old enough to remember the unpaved back lanes that flooded every spring. Two formative events in the North End not mentioned in the article were the 1919 Strike and, less often noted, the tearing out of the street care tracks along Main Street. In the 1980s when I was Deputy Minister of Community Services in the Pawley government we ‘blew up’ the Winnipeg Children’s Aid Society and established five decentralized ‘Child and Family Service Agencies’ across the city, including one in the North End - with its HQ in the old Bank of Montreal building on Main and Bannerman (I think that was the cross street). Over 3000 people turned out for the election of the first Board. I think the agency could have made areal difference in the North End, as it included strong representation from within the Aboriginal community and took on a significant preventive mandate, but the Filmon government took over and got rid of all the agencies after a little more than a year, so we will never know what might have been. We did however fund the community effort to set up Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre which remains to this day. So perhaps it was not all for naught.

#4. Posted by Michael Mendelson in Toronto on February 8th 2010 at 6:17pm

Michael Mendelson speaks of the New Democratic Party Manitoba government led by Howard Pawley and just a few of its important initiatives of which there were many—- probably the most honest government in the history of the North American continent. He then goes on to mention how the thoroughly reactionary government of Gary Filmon destroyed several of the Pawley government’s programs of which there were so many destroyed by the Filmon government which leads me to wonder why no one has yet written a comparison of these two governments.

It seems to me now would be the time to write such a comparison.

I was living in Manitoba for about ten years at the time the Filmon government was coming into power. Filmon privatized the Manitoba Telephone Service and Manitobans are still suffering the consequences.

But, Filmon also did, what I consider to be one of the most callous and anti-human things imaginable in putting an end to the dental program in the elementary schools.

If every government in the world was just one iota as honest and caring about the needs of working people as was the Pawley NDP government, people could be living pretty decent lives.

There is a story that needs to be told here—- a tale of two governments; one for the people, the Pawley NDP government—- the other, the Filmon Government of Progressive Conservatives for the greedy wealthy few and the corporations.

(Now there—- Progressive Conservative—- is a real oxymoron if ever there was one.)

A webb site or blog would be the perfect place to tell this story of a tale of two governments. Working people across North America need to know and understand this story which is the history of the clash and struggle between classes.

This is an especially important story to tell at a time when working people are beginning to think there is no hope for change while taking such beatings and are being battered by Bay Street and Wall Street.

Working people across North America need to experience the all-inclusive government like that of Howard Pawley’s government which welcomed a full and complete expression of just about every political view from liberal to socialist to communist represented in the various people’s movements… proving people working together accomplish great things.

When people tell me about “hope” and “change” here in the United States, I always tell them: You don’t know what “hope” and “change” is all about unless you understand the people’s movements that brought governments like that of Howard Pawley, Tommy Douglas, Floyd Olson and Elmer Benson to power.

Unlike the Tommy Douglas story or the history of the socialist Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, the story of the Howard Pawley NDP government is still fresh enough to become an important factor in the struggles of today. Tell the story.

#5. Posted by Alan L. Maki in Warroad, Minnesota, USA on February 25th 2010 at 9:44am

Alan

Winnipeg’s North End

Yesterday and Today

By: Jim Silver

January 7th 2010

http://canadiandimension.com/articles/2674/

Winnipeg’s Historic North End. Photo Courtesy of The Winnipeg Tribune / University of Manitoba Archives.

Elsie Strewchuk stands behind the counter of the North Main Groceteria that she and her husband opened in 1954. Photo Courtesy of The Winnipeg Tribune / University of Manitoba Archives.

Poverty in the North End today. Photo by Jon Schledewitz

Winnipeg’s historic North End was a contradictory place. Poverty was widespread and deep; out of its midst grew a rich and vibrant culture. Today’s North End is similar in many respects — deep poverty and racism, and an emergent culture of resistance, for example — yet different in important ways.

Poverty in Winnipeg’s Historic North End

After 1896 Eastern European immigrants arrived in large numbers in Winnipeg, settling in the North End to work in the vast rail yards and associated industries. Housing was inadequate and terribly overcrowded. The 1908/09 Annual Report of All-Peoples’ Mission, then headed by J. S. Woodsworth, said of a part of its North End neighbourhood: “in 41 houses there were 120 ‘families,’ consisting of 837 people living in 286 rooms,” more than 20 people per house. Overcrowding, plus half the North End houses not being connected to the water supply, produced disease: in 1904 and 1905 Winnipeg had more deaths from typhoid than any North American city. A 1913 study by Woodsworth found that a “normal standard of living” required wages of $1,200 per year; many in the North End were earning less than half that.

Most people were working; they just didn’t get paid enough. Others worked seasonal jobs on farms or railway construction and endured cold, hungry winters in Winnipeg.

Winnipeg was deeply segregated, a city divided, the North End cut off from the rest of the city by the vast CPR yards and distinguished by its “foreign” character. A 1912 publication described the North End as “practically a district apart from the city,” adding that “those who located north of the tracks were not of a desirable character.” The largely Eastern European working class residents of the North End were called “dumb hunkies,” “bohunks,” Polacks; anti-semitism was rampant.

In Under the Ribs of Death, John Marlyn’s novel set in early twentieth Winnipeg, Sandor Hunyadi, a young Hungarian immigrant, lives in the North End, described as “a mean and dirty clutter … a howling chaos … a heap seething with unwashed children, sick men in grey underwear, vast sweating women in vaster petticoats.” When the young Sandor visits Crescentwood, the south end home of those of Anglo-Saxon descent who controlled the political and economic resources of the city, he was shocked to see that “the boulevards ran wide and spacious to the very doors of the houses. And these houses were like palaces, great and stately, surrounded by their own private parks and gardens. On every side there was something to wonder at.”

Much was extremely positive about the North End. Selkirk Ave was a thriving commercial street with a dazzling variety of shops and stores whose owners typically spoke several Eastern European languages. A rich and varied cultural life characterized the North End: newspapers published in many European languages; literary associations, drama societies, and sports clubs; a wide range of alternative schools; and according to one author, “a music teacher in every block in the North End to give the Jewish, Ukrainian, and Polish kids massive degrees of musical instruction weekly.” There was a thriving co-op sector, mutual aid societies, a labour temple, and radical politics of a bewildering variety of kinds.

Most of this was invisible to those outside the North End, but as Roz Usiskin has put it, from this vibrant culture North End residents “derived a dignity denied them by the dominant society.”

Post-War Change in the North End

In the post-Second World Large numbers of North End residents who could afford to do so moved to the larger, newer houses and greener spaces of the suburbs. Businesses andcultural organizations followed; economic and cultural life in the North End atrophied. Housing prices dropped; many became rental properties, some owned by slum landlords.

By the late 1960s-1970s manufacturing began to leave, and the character of the labour market shifted, with full-time unionized industrial jobs gradually being replaced by part-time, non-union, low-wage service sector jobs.

Just as these broad social forces — suburbanizationand de-industrialization — were unfolding, Aboriginal people began migrating to western Canadian cities, and especially Winnipeg, starting in the 1960s and growing by the decade. In 1951 there were 210 Aboriginal people resident in Winnipeg; in 1961 there were 1,082. By 2006 there were 68,380, the largest urban Aboriginal population in Canada. Many Aboriginal people located in the North End, attracted by cheap rental housing. When they arrived they were, generally speaking, ill-prepared for modern urban life, the result of a century of marginalization, colonization, and the damage inflicted by the residential schools. They arrived just as the good jobs were leaving, to the suburbs or out of Winnipeg entirely. And upon their arrival they faced a wall of racism.

Aboriginal people have replaced Eastern European immigrants as the poor and frequently reviled residents of the North End. They face the same racism and exclusion today that the newly-arrived Eastern European workers and their families did early in the twentieth century. They experience similarly inadequate and over-crowded housing conditions — the result of the severe shortage of low-income rental housing all across Canada that is accentuated in Winnipeg’s now sprawling inner city.

They have suffered racist abuse for decades. In a 1962 Winnipeg Tribune story, Jarvis Ave., just north of the CPR yards and previously the heart of the pre-Second World War Jewish North End, was described as “the worst street in the entire city.” Houses had long been little more than shacks; many of the small lots had two or more dwellings squeezed onto them. The Tribune story began: “The police, with ponderous legal irony, call it Jarvis Boulevard. Others, with more bitterness, have called it Tomahawk Row.” Aboriginal newcomers had located there, in search of low-cost housing. Their socio-economic circumstances were the root cause of problems in the area.

But, like their Eastern European working class predecessors who had occupied the same neighbourhoods before them, they were blamed for their poverty. A half-century earlier, in 1912, Winnipeg’s Associated Charities Bureau had written, referring to the Eastern European working class immigrants squeezed into inadequate North End housing and underpaid as they were, that “the large majority of applications for relief are caused by thriftlessness, mismanagement, unemployment due to incompetence, immorality, desertion of the family and domestic quarrels.” Such simplistic and stereotypical claims echo across today’s North End.

These things about Winnipeg’s North End have not changed. It is home to deep and widespread poverty; those who are poor are reviled and blamed for their own fate; and the North End remains spatially and socially segregated from the rest of the city. Many in Winnipeg do not venture into today’s North End; most are largely ignorant of life in the North End; it has ever been thus.

It’s Still the Same, but Different

Whereas the poverty of the early twentieth century North End was a working class phenomenon, today, because of dramatic shifts in the global economy, a much higher proportion of those in poverty are the jobless poor, largely outside of and in many cases with little or no experience of the paid labour force. This is disproportionately the case for Aboriginal youth, and is a source of many problems. Massive, publicly funded job creation is needed.

The North End poor of the early twentieth century typically lived in and benefited from intact, two-parent families, and ethnic cultures that were a source of strength and pride. Today, a much higher proportion of those who are poor live in families and communities that are less strong and resilient than was the case in the past, and in many cases their cultures have been seriously damaged. In the case of Aboriginal people, this is the result of the historic and contemporary process of colonization, by which the Canadian state set out deliberately to destroy Aboriginal families and cultures.

The route out of poverty taken by many of the descendants of the Eastern European working class is less readily available to the disproportionate numbers of today’s North End poor who are Aboriginal. Eastern Europeans were able to, and wanted to, assimilate into the dominant culture. Aboriginal people are less able to assimilate, less able to escape racism than their White predecessors in the North End, and less willing to do so.

The poverty of today’s North End has changed dramatically because of the intensified crime that plagues the inner city. Street gangs, the illegal drug trade, and damage done to families and cultures, and the almost complete disconnection of large numbers of young people from the labour market, have created a serious problem of crime and violence that is qualitatively different, and worse, than what existed in the North End during earlier periods of the twentieth century.

Finally, the poverty of today’s North End is experienced by many as a sense of hopelessness, of deep and dark despair. Inadequate housing, deep poverty, the prevailing crime and violence, the absence of jobs that pay a wage sufficient to support a family, have created a “spiritual” malaise among many that is particularly debilitating.

In many respects, today’s North End is unchanged from that of the early part of the twentieth century: deep poverty; widespread racism directed at the poor; their spatial segregation in a devalued part of the city. In other respects, it is different, perhaps even worse: the disconnection from a changed labour market; the erosion, in many cases, of families and cultures; the widespread crime and violence; the deep sense of despair and hopelessness amongst many.

Rebuilding from Within

These poverty-related problems notwithstanding, there is a dramatic process of rebuilding from within that is currently underway in Winnipeg’s North End and broader inner city. Like the vibrant culture of the early twentieth century North End, it is largely invisible to those who do not live there. It takes the form of a wide range of community-based organizations that have emerged from the ground up, and that use a community development approach to heal and empower those who are poor and have been damaged by poverty, racism, and colonization. Aboriginal people and Aboriginal women in particular are among the leaders in this work. The best of their efforts is aimed at rebuilding awareness and appreciation of their rich cultural heritage. Women’s centres of a wide variety of kinds, family resource centres, alternative educational institutions and neighbourhood development organizations are all part of an increasingly strong infrastructure of community-based organizations. Their work is creative and innovative; they hire local people thereby creating employment opportunities; they work in a way informed by their workers’ and leaders’ own experience of poverty and racism.

This rebuilding process is slow and difficult. For every step forward, another is taken back. It would be faster and less difficult with more public sector support. The civic and federal governments are largely absent from this process. The provincial NDP government has been supportive in many important ways. They have not done and still do not do enough to nurture and support this indigenous rebuilding process, but they have been quite supportive in some very important ways, and would be likely to be more so if they thought that there was public support for a stronger anti-poverty strategy.

The North End and the Left

The anti-poverty strategy that has emerged out of Winnipeg’s North End and broader inner city over the past quarter-century has not taken a form familiar to most leftist readers of Canadian Dimension. It has been and is being built by the poor themselves, and has taken a form that they have defined, and that has grown out of their realities. The labour movement is largely absent from this struggle; the far Left, to the extent that it exists at all in Winnipeg any longer, is absent from this struggle.

It is striking, however, that growing numbers of progressive young people are becoming interested in and active in this struggle. Although what follows is impressionistic, it may be that many young people recently energized by the anti-globalization movement have now turned their attention to local, community-based anti-poverty struggles in the North End and broader inner city.

If young, urban Aboriginal people were also to become politicized as part of this struggle, and were to begin to mobilize around demands related to antipoverty efforts, the pace of change would surely accelerate. There are few signs yet of that happening, and in fact an Aboriginal middle class is emerging, anxious to distance themselves from the poverty and related problems of the North End.

Yet there is deep anger in Winnipeg’s North End, the product of poverty, racism, and segregation. Much of that anger is inner-directed, in such forms as addictions and domestic abuse, but also in the form of increasingly severe street-level conflict and violence confined largely to the North End and directed largely at other North End residents, and frequently at police.

Most Winnipegers, spatially and socially segregated from the North End and its residents and steeped in stereotypes previously used to describe Eastern Europeans, are removed, in every respect, from these issues. If they could be mobilized in support of genuine, publicly-driven anti-poverty efforts, and/or if North End youth, and especially Aboriginal youth, were themselves to become politicized and direct their anger outwards, real gains could be made in the North End. Until that happens, and despite the exceptional community development efforts in the North End, change will be unbearably slow, and will come too late for many.

This article appeared in the January/February 2010 issue of Canadian Dimension magazine. SUBSCRIBE NOW to get a refreshing and provocative alternative delivered to your door 6 times a year for up to 50% off the newsstand price.

5 comments

I live in the South End of Nanaimo, which is considered the skuzziest neighborhood in the city. Yes, you do see some poor young girls in the sex trade walking down Victoria Road, and that is because men in fancy cars from the North End come looking to exploit their drug addictions which were induced by some other exploitative men. On what is considered THE worst block in this city, a couple of blocks from downtown, my friend just bought an 80 year old house, a Craftsman, which has unsurpassable charm. Three stained glass windows, original fir floors in good condition, coved ceilings, french doors with etched leaded glass panels, a sun room with windows on 3 sides, which leads to a sundeck with a sweeping view of the estuary and Gabriola Island, and spectacular sunrises which are reflected on the water. There is a walk-in closet off the master bedroom. There is a little inner courtyard outside, and a peach tree and 2 Kiwi fruit trees, and a fish pond in the yard. Next door to her live 4 men who are a brass quartet, and they have a big old boat in their backyard. My point in all this is that it is possible to find beauty and charm where you least expect it, and it doesn’t have to be about big money at all. In fact there can be something ugly about big money neighborhoods - the pretentiousness of them, and the lack of originality, spontaneity, history, and variety.

#1. Posted by Madeline Bruce, RPN in Nanaimo, B. C. on January 8th 2010 at 4:35pm

So , it would seem to me to solve the problem of poor people living in the North End, would be to double the rents to get rid of the poor .

#2. Posted by rosencrentz in winnipeg on January 28th 2010 at 6:58pm

No, that doesn’t sound nice at all. Speaking for South Nanaimo, the poorer section of Nanaimo, the price of houses and rentals is lower than the rest of Nanaimo. Gradually the old houses are being re-vamped, which makes for a very charming ambiance. As for unemployed people, many impoverished people are employed - just not getting enough hours, or enough wages. As for the chronically underpriviledged, some kind of entreprenurial initiative is needed to help them. Perhaps the teaching of new skills by retired people, which they could then market themselves, would get them on the road to a renewed self-confidence and hope for the future.

#3. Posted by Madeline Bruce, RPN in Nanaimo, B. C. on January 28th 2010 at 7:32pm

I enjoyed reading this article and found it very thoughtful. I grew up in the North End in the 1950s and 60s, spending all my time hanging around at the Sals and Sportsman’s. I am old enough to remember the unpaved back lanes that flooded every spring. Two formative events in the North End not mentioned in the article were the 1919 Strike and, less often noted, the tearing out of the street care tracks along Main Street. In the 1980s when I was Deputy Minister of Community Services in the Pawley government we ‘blew up’ the Winnipeg Children’s Aid Society and established five decentralized ‘Child and Family Service Agencies’ across the city, including one in the North End - with its HQ in the old Bank of Montreal building on Main and Bannerman (I think that was the cross street). Over 3000 people turned out for the election of the first Board. I think the agency could have made areal difference in the North End, as it included strong representation from within the Aboriginal community and took on a significant preventive mandate, but the Filmon government took over and got rid of all the agencies after a little more than a year, so we will never know what might have been. We did however fund the community effort to set up Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre which remains to this day. So perhaps it was not all for naught.

#4. Posted by Michael Mendelson in Toronto on February 8th 2010 at 6:17pm

Michael Mendelson speaks of the New Democratic Party Manitoba government led by Howard Pawley and just a few of its important initiatives of which there were many—- probably the most honest government in the history of the North American continent. He then goes on to mention how the thoroughly reactionary government of Gary Filmon destroyed several of the Pawley government’s programs of which there were so many destroyed by the Filmon government which leads me to wonder why no one has yet written a comparison of these two governments.

It seems to me now would be the time to write such a comparison.

I was living in Manitoba for about ten years at the time the Filmon government was coming into power. Filmon privatized the Manitoba Telephone Service and Manitobans are still suffering the consequences.

But, Filmon also did, what I consider to be one of the most callous and anti-human things imaginable in putting an end to the dental program in the elementary schools.

If every government in the world was just one iota as honest and caring about the needs of working people as was the Pawley NDP government, people could be living pretty decent lives.

There is a story that needs to be told here—- a tale of two governments; one for the people, the Pawley NDP government—- the other, the Filmon Government of Progressive Conservatives for the greedy wealthy few and the corporations.

(Now there—- Progressive Conservative—- is a real oxymoron if ever there was one.)

A webb site or blog would be the perfect place to tell this story of a tale of two governments. Working people across North America need to know and understand this story which is the history of the clash and struggle between classes.

This is an especially important story to tell at a time when working people are beginning to think there is no hope for change while taking such beatings and are being battered by Bay Street and Wall Street.

Working people across North America need to experience the all-inclusive government like that of Howard Pawley’s government which welcomed a full and complete expression of just about every political view from liberal to socialist to communist represented in the various people’s movements… proving people working together accomplish great things.

When people tell me about “hope” and “change” here in the United States, I always tell them: You don’t know what “hope” and “change” is all about unless you understand the people’s movements that brought governments like that of Howard Pawley, Tommy Douglas, Floyd Olson and Elmer Benson to power.

Unlike the Tommy Douglas story or the history of the socialist Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, the story of the Howard Pawley NDP government is still fresh enough to become an important factor in the struggles of today. Tell the story.

#5. Posted by Alan L. Maki in Warroad, Minnesota, USA on February 25th 2010 at 9:44am

Labels:

community renewal,

jim silver,

north end,

winnipeg

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment